Thoughts on Thailand

Out of all the countries we visited on our trip around the world, Thailand was the one in which we spent the most time. 61 days, over two visits. It has since gone down on our list of places we want to return to someday, but when we first arrived, we were not impressed.

We had been traveling fairly quickly ever since Africa and by October we were both ready for a break. While we were still in Russia, we planned out the last three months of our trip. In order to conserve money – we had just officially gone over our travel budget – we wanted to find a place to sit down and rest for a while. I sent out a request on Facebook and Twitter and asked our friends and followers for their recommendations in Thailand.

We received a lot of good advice, but ultimately had a hard time taking advantage of it because we were set on a month-long rental. We checked Craigslist and various vacation rental websites, but the vast majority of listings were only available in the largest cities or most touristy areas. We debated traveling out to the remote islands until we found a place to our liking, but ultimately took the easy way out. We spent just a couple days in Bangkok, recuperating from our jet lag, before flying to Phuket and following up on some leads there.

The first place we stopped was in party central, Patong. I can’t even remember why we chose that town, because foam-party nightclubs, seedy massage parlors, and plentiful weed are not on our list of travel necessities. Nevertheless, Oksana found us a cheap hotel away from the beach, and we stayed there a week.

Prices were low, as October is still officially the off-season. And no wonder – it rained hard just about every day we were in Patong. That didn’t bother me especially much because I had just come down with my first cold since leaving home almost a year and a half before. For the next week, all I wanted to do was lie in bed and sleep. Easier to do during the day – night were miserable… at least until I visited the pharmacist, a real life anime character, who prescribed me some heavy sleeping pills.

Unfortunately, just as I was about to get over my cold, Oksana picked it up. Most of our month off was spent battling head and chest colds.

Eventually, we left the Starbucks and McDonald’s behind by moving just four kilometers down the island to Karon Beach. The oceanfront was prettier, the tourists more family oriented, and both of those things suited us just fine. For about $19 per night, we stayed in a huge hotel room, venturing out once a day to the pool or to place an order at the on-site restaurant. We caught up on some internet stuff, rested our travel-worn feet, and worked on our tans.

Prices went up on November 1st with the official start of the high season, but we didn’t mind. Our friends from Roam the Planet were due to arrive any day and, with our batteries recharged, we were ready to hit the road again.

Because of the record flooding that was going on in central Thailand during our stay, we didn’t get to see as much of the country as I’d hoped. Most of the things I noticed about Thailand came from the few places we did spend some time: Bangkok, Phuket, the Phi Phi islands, Chiang Mai, and Koh Mak.

Hello!

“Have you showered yet today?”

That’s apparently a colloquial greeting in Thailand. Kind of like, “Hey, how’s it going?” When our host in Koh Mak told me that, I had to get the full story. How in the world does “Have you showered yet today?” mean “Hello?”

He explained that it’s very hot and humid in most parts of Thailand and when welcoming someone into your home, it’s considered polite to offer them the opportunity to freshen up before socializing.

That makes sense, I suppose. Definitely more than “How’s it hanging?” or “What’s up?”

Bowing

You’ve probably seen the typical Thai greeting, or wai, in movies or on television at some point. Palms together, prayer-like, accompanied by a short bow. Not knowing what was socially expected of me, I usually just nodded my head in response and said “thank you” or “hello,” whichever seemed more appropriate at the time.

Reading up on it now, I see that there’s a lot of room for nuance in the gesture. How close the hands are to the face, how deep the bow goes. I guess if you’re being polite, you’re also supposed to perform a wai when asking permission to leave someone’s house. All these unspoken rules remind me of the warning to never point your foot at another person. Just another peculiarity of the Thai culture.

As an American uninitiated to their culture, I something think I must have been the equivalent of man swaggering down the street, middle fingers raised to shoulder height, belching and farting at everyone that passed.

Dancing

Can you picture a traditional Thai dance? The slow, undulating movements of colorful and elegantly dressed women? The lithe and gentle movements from the wrist and elbow, the tips of the fingers lightly touching and forming intricate shapes? I think of it as a “hand dance,” though I doubt that’s what it’s called.

We were discussing this dance with a couple from Oxford who happened to be traveling on the same bus one day. Zissy (I think her name was; wish we’d exchanged contact info!) wondered aloud if the slow and meticulous dance could be a result of their living in a hot climate. It wouldn’t take much to work up an unsightly sweat in Thailand.

What a fascinating idea! We started comparing other cultures’ traditional dances. Do colder climates have more energetic dances in order to raise the body temperature? I couldn’t help but think back to a cold night on an island in the middle of Lake Titicaca, where our entire Spanish class was pulled into a scene straight out of National Geographic. While the Quechua men got drunk and played their instruments, the women cut loose and dragged us onto the darkened city hall, their makeshift dance floor. Their dances were all energetic skipping in woven formations while legs and arms pumped up and down. The musicians must have been jamming – I swear each song lasted at least 15 minutes. We were dying from the altitude.

Anyway, I think Zissy might be on to something. There’s got to be a doctoral dance thesis in there for someone.

Photography

I learned to travel at the same time I learned to take pictures. I bought my first 35mm SLR just before going to Ecuador, which was essentially just my second trip out of the country. In hindsight, I regret that my eye for composition developed in Latin American countries. Why? Because I learned not to point my camera at people.

In most of Latin America – South America especially – it’s considered rude to take someone’s photo without asking. I can understand why. If you’re a photogenic, traditionally-dressed Peruvian living in, say, Cusco, you’re going to have a lens shoved in your face every day of your life. It’s like being famous – stalked by paparazzi! – without any of the perks.

So as I was learning to use a real camera, my subjects were ruins and landscapes. I always felt guilty when I tried to take market photos and saw all the vendors turn their heads and hide behind upraised arms. Sure, I could buy something from them first, or give them a “tip,” but I wouldn’t capture anything spontaneous or candid if I did.

In Thailand, I noticed, everyone liked having their picture taken! At the Festival of Lights, we’d get right up close with our cameras and they would actually stop what they were doing and pose for us. As we walked alongside a parade, you could tell the participants on the floats would actively seek photographers out. They’d lock eyes with you, through the viewfinder, and then nod and smile after you lowered the camera. It was a novelty for me.

(Oksana, by the way, is much better at people photography than I. I would guess that she took most of the people photos you’ll find in our photo albums.)

Language

Let’s get this out of the way right now: There’s no standardized way to spell Thai words with the Roman alphabet, but place names with a “ph” in them are most definitely not pronounced with an English “F” sound. The “h” in “Phuket” is pronounced as a tiny puff of air, hardly said at all: “Pahoo-KET.” So, no, you can’t have much fun with the name of that island. Don’t worry. We’ll always have Koh Phi Phi.

I thought it would be Africa or Eastern Europe that would have tripped us up, but Thailand was the first country in which we really had difficulty communicating. Just like anywhere else, there are plenty of people who speak English circling around the tourism industry. It was when we left that protective bubble that we were in trouble.

In the Thai language, simple, monosyllabic words can be have different meanings depending on the tone in which they are said. The five basic tones are easy to remember. They are rectus, gravis, circumflexus, altus, and demissus. Ha ha, just kidding! They’re also called mid, low, falling, high and rising.

Think of it this way: The word “mai” can mean either “wood,” “silk,” “burn,” “new,” or “not,” depending on how you pitch your voice when you pronounce it. I remember a story my uncle told me about learning the language in a classroom (he lived in Thailand for a couple years in the early 70s.) His whole class was driven crazy by a single, tone-deaf student endlessly repeating the instructor’s words in a flat monotone. Thai would be hard (for me) to learn. I can hear the different tones; I just can’t keep them straight in my head.

If you’re at all interested (and like having your mind blow), watch the first minute of this video on Youtube (decide for yourself if you want to continue after that; it only gets more confusing as you go!)

Thai Language Lessons: Tone Rules Explained

In all honesty, it was even difficult for me to speak English with Thai people. For one thing, it was almost literally impossible for them to pronounce my name.

“Arlo.”

“Aaah-ro?”

“No. Ar. Lo.”

“Arrrooo?”

“Close. Ahr. Lho.”

“Allll rrrro?”

“Okay, sure. Let’s move on.”

(I didn’t take offense; I couldn’t pronounce their names, either.)

Just listening to the musicality of the language, it seems to me that Thai is all about the vowels. Words flow into sentences very smoothly and consonants are rarely harsh or abrupt. Because our own languages influence how we learn others (which is why practically everyone has an accent when they speak in a foreign language), Thai people can be especially difficult for an American to understand, even when they’re speaking English.

I once stopped in at an airport McCafé to grab some drinks to take to the gate with us. I asked for a mango tea and a caramel macchiato. The girl behind the counter looked up and asked, “Aaah oh eye?”

“Excuse me?”

“Aaah oh eye?” she repeated.

“I’m sorry, I don’t understand.” I looked quizzically at the other girl standing behind the counter.

“Aaah oh eye?” they said in exasperated unison. “The macchiato. You want it aaah or eye?”

“Oh, ‘iced!’ Yes, I’d like it iced please!” Hot or iced. I was blushing in embarrassment as I paid for the drinks.

Apparently, this is a common problem. The next time I tried to order something in a McDonald’s, they slid a big, plastic, picture menu across the counter and asked me to point and what I wanted.

The only other interesting tidbit I have about the language is that people in northern Thailand are able to speak with people from Laos. I asked the woman who ran our hostel in Chiang Khong if it was the same language. She said it wasn’t, but explained that Northern Thai (there are four distinct Thai dialects) is about 90% the same as Laotian… or at least the Laotian dialect they speak right across the border.

“Wat,” did you say?

I always thought the word “wat” meant “temple” in Thai. Turns out, it means “school.” Which makes sense, when you consider all those temples are actually monasteries.

I don’t know much about Buddhism, monks, or wats, but I enjoyed taking pictures of those monasteries. The architecture Thais use in their places of worship is so colorful and ornate! Plus there are dragons and elephants and demon warriors!

Food

How can I write about Thailand and not mention Thai food? Looking over my notes, it’s surprising how many things fall into that category.

I assume most people are already familiar with Thai food. I’ll just say that I was surprised how much better it can be in the country itself. When their curries and soups are made with fresh local ingredients, it’s like everything I had before was a shadow of what it could have been. Plates are cheap (though portions are small by American standards) and we tried everything from seafood to chicken to pork and beef. Overall, Thailand is a delicious country in which to find oneself, but that doesn’t necessarily mean everything is good…

Oyster Sauce

What exactly is oyster sauce? It’s on every table in Thailand. Is it for oysters or made from oysters? You know what? Either way, it’s not for me.

Mayonnaise

There’s not a lot of mayo in Thai food, but we were living there for a month and there were certain things we stocked up on. One was mayonnaise, or whatever that creamy white stuff they call mayonnaise is over there. Sorry, but mayo shouldn’t be sweet.

Dyed Food

When we first arrived in Thailand, both Oksana and I noticed some unnaturally bright and colored foods in the markets. Inky wet fruit that looked like it would stain your clothes, candy-green mussels spread out on ice, eggs and lettuce that were a shade of green I’ve never seen in nature before.

At first, I would have sworn up and down that they’d been dyed to make them look more appealing on display, but after two months in the country and seeing the same colors in different cities, I’m starting to wonder if that might not be the case. Who knows? Maybe the colors are just brighter over there!

Fruit

I thought the jungles of South America had the best, most exotic fruit in the world. I was wrong.

What fun we had touring the fruit markets of Thailand! Our favorite fruit there, hands down, was rambutan. I’d never seen it before a trip to Ecuador a couple years ago and introduced Oksana to it in Zanzibar last year, where they called it mshokishoki. The red and yellow fruits are covered with soft spines and contain a seed inside, surrounded by sweet white flesh. You pop them open, eat the flesh and spit out the seed. Rambutan are nature’s gummi bears.

Oksana sampled everything. There were dragonfruit, which was kind of bland, but looked like cookies and cream flavored ice cream on the inside. Tamarind grew in long pea-pods, but dry and brown like a giant, segmented peanut. Inside were sticky red seeds surrounded by a network of ropy red veins reminiscent of that alien fungus in the latest War of the World’s remake. Lycee was like rambutan’s less flamboyant sister, while Longan fruit was its dull, earthy brother. And of course, there’s durian, which smells as bad as you’ve heard, but actually tastes better than you’d expect. Kind of like a citrusy-banana-y kind of thing. I never tried sugar apples nor purple mangosteen, but Oksana said they were both good, too.

Bananas, pineapples, papayas, coconuts, mangos, guava, melons, jackfruit, oranges, pomelos, starfruit (carambola), and strawberries: Thailand also has all the things we’re already familiar with. It’s a fruit-lover’s paradise!

Bread

Throughout our travels, Oksana and I have made it a habit to seek out decent bakeries. I enjoy stopping by in the morning and grabbing a quick and inexpensive breakfast to go. At some point we realized that we hadn’t come across a single bakery in Thailand.

I’m sure they exist, but it’s rather surprising how little Thais use bread in their cuisine. I got to wondering why that is and realized that it probably has something to do with rice.

When we flew into Bangkok, I remember looking out the window and seeing nothing but miles and miles of flat land, endless fields filled with nothing but water and rice. Seeing all that stagnant water, I couldn’t help but think about snakes and mosquitoes and how we skipped our Japanese Encephalitis vaccinations. I wondered why Thailand didn’t raise a less water-intensive grain…

…and then I realized I had it the wrong way around. The heavy monsoon rains that hit Thailand every year mean that rice is the only thing they can grow. So maybe a lack of wheat is one reason they don’t have much bread in Thailand. Or it may just be that all the noodles they eat fulfill the same dietary requirements. At any rate, we wouldn’t find a decent bakery again until Laos.

Drinks

The drinks in Thailand – the soft drinks and juices and such – are amazing. I don’t know what they are, but they’re amazing.

The cooler section in the stores are filled with dozens (if not hundreds) of varieties of drinks. I wish I could tell you what they all were, but often they didn’t have any English on the label. Those that did were often meaningless. “The Original Soy Peptide: Peptein!” What do you suppose that tastes like?

Oksana and I experimented a bit the first month we were there, but when our friends arrived, we recruited them into sampling some of the crazier stuff with us. We recorded a video of the drinking game we played.

Aphrodisiacs

If, despite the ubiquitous prostitutes, go-go bars, and seedy erotic massage parlors, you somehow missed the fact that Thailand was a sexually liberal country, all you’d need to do is check out the coolers in the local grocery stores. Sprinkled in among all those crazy Thai drinks are a huge variety of liquid aphrodisiacs. Granted, many of them are probably just energy drinks marketed toward a different crowd, but still. Would you want to be seen sipping on a tiny vial of something called “Hang Foreplay?”

Straws

Every time you buy a drink at the store, whether it’s a soda or a juice or an iced coffee, the cashier will hand you a straw. They have tons of them up by the counter. Makes me wonder about the sanitary condition of the lids – we definitely found a few cans of Diet Coke with crud smeared all over the top. We felt safe drinking from the plastic bottles, however.

Beer

Thailand doesn’t have a lot of variety in its beer. You’ve basically got three big brands to choose from: Chang, Singha, and Leo. To me, a micro-brew only kind of guy, they all taste about the same. Bad, that is to say. Except that, on a really hot day, and when the beer is really cold, they somehow transcend their badness and become pretty good.

But that’s neither here nor there. What surprised me about beer in Thailand is that they often serve it over ice. That’s just weird.

Service

When Oksana and I ate out together, I’d say there was a 50/50 chance we’d be served at the same time. When we ate out with our friends, it never happened. In Thailand, they serve food when it’s ready and the cook doesn’t make much of an effort to time the dishes so they hit the plates at the same time. This often resulted in four hungry people waiting for the last person to be served while pointedly ignoring the delicious, cooling food in front of them.

Eventually we made a pact. Forget being polite; eat when you’re served. Besides, Thai food is meant to be shared around the table anyway.

Cinemas

I’ve been in some good movie theaters in my time, but nothing like they have in Bangkok. I’d trade every Cineplex and IMAX I’ve ever been in to have a good Thai theater near my home. They’re amazing.

Oksana and I only had the opportunity for one high-end cinema experience, when we watched Contagion in a Nokia-sponsored “Ultra Screen” in Bangkok. It cost us $45 USD just for just the two tickets, but that was okay, because it was almost a religious experience.

First, we were given the option to relax in a comfortable lounge where an usher promised to escort us to our seats just before the previews and commercials ended. Our seats were leather recliners paired off and separated from the other 20 seats in the room by a semi-circular divider. There were even pillows and blankets, if we wanted to get more comfortable.

One thing you have to do in a Thai cinema, however, is rise for the national anthem that plays as a music video just before the movie begins. “Long live the king!”

I get the impression that Thais really get the cinema experience, too. They’re very respectful during the movie. They don’t talk or use their cell phones. Hate to say it, but I think I value their cinema culture even more than the U.S.’s.

May be a good thing we don’t have many theaters like that in the States, though. I’d blow my paycheck every weekend.

Shoes

Everyone takes their shoes off when they go inside. Everyone.

Surprisingly, even the hotels and hostels we stayed at contained two pairs of flip-flops so no one would have to walk around barefoot. In that respect, it was a lot like Russian homes.

But in Thailand, they take it to extremes. All of the temples (sorry, wats), as well as most of the smaller businesses – dentists, doctors, offices, dive shops – request that you to leave your shoes at the door. Fortunately, restaurants and supermarkets had no such rules.

“No shirt, shoes(!), no service!”

Fingernails

In Thailand, it’s not uncommon to see a man with a pinky fingernail grown out to ridiculous lengths. Having grown up in the 80s, all I could think was “cocaine user.” That couldn’t be it, though.

Turns out, it’s most likely a symbol of social status. People who have to do hard, physical labor for a living are not able to grow their fingernails out. If, on the other hand, you have a nice white collar job (or whatever the equivalent is over there), then I guess a well-manicured pinky nail is something you can devote your time to maintaining.

That and, the internet tells me, they’re good for extracting boogers and earwax.

Personal Safety

There are plenty of rundown neighborhoods in Thailand, but Oksana and I never felt threatened walking through them. After awhile, we lost a bit of our street paranoia because we just didn’t feel like we were ever in danger there. Granted, there are plenty of places in the seedier parts of Bangkok or Pattaya where stupid or drunk tourists are involuntarily separated from their money, but we didn’t frequent those places.

The biggest crowd we ever wiggled through was during the Festival of Lights in Chiang Mai. It was chaos. Five of us spent two or three hours wandered around the river, most of our attention focused on our cameras settings. I worried about my backpack, constantly being bumped and nudged, and my shorts’ pockets filled with wallet, iPhone, and GPS. Nothing was lost. We discussed it later and decided that none of us felt like there were any pickpockets lurking around at all. Except for the fireworks exploding around us, the whole night felt quite safe.

(We also realized that hardly anyone was drinking! A huge, city-wide celebration and only a handful of obnoxious British hooligans to spoil the mood.)

Transportation

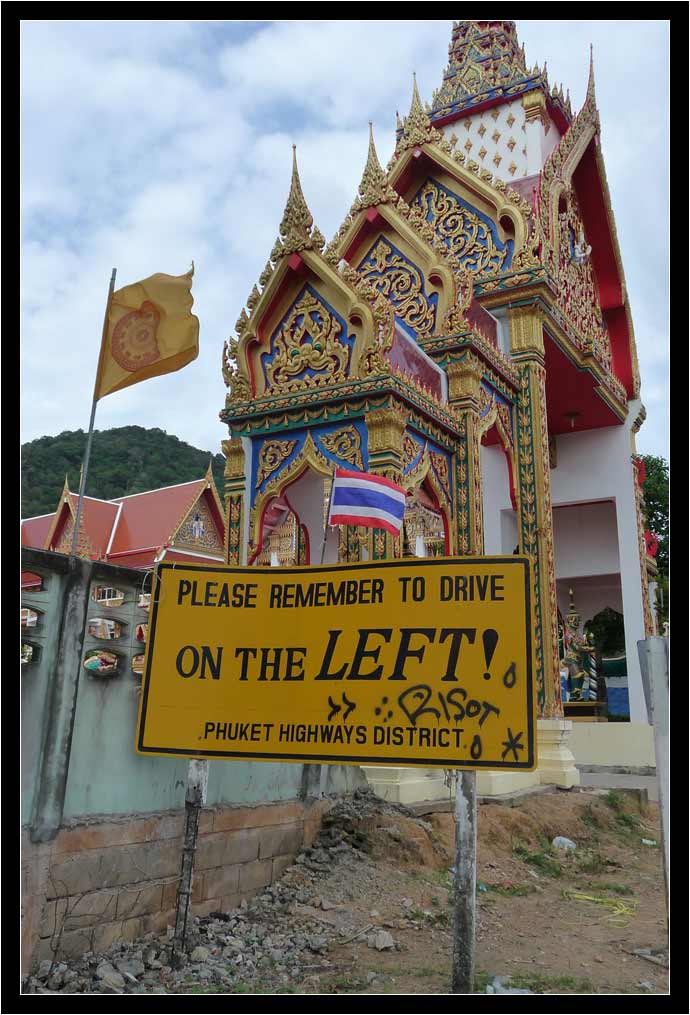

Traffic, in many ways, was different in Thailand, but there were some similarities to the way we do things in America.

First thing you notice is that they drive on the left. (Well, I guess that would be the first time you’d notice if you were coming straight from the U.S. After 31 countries, we’re thoroughly confused. I can no longer remember which countries drive on which side of the road.) The second thing you notice is that the direction of travel is really only a suggestion. We saw plenty of people nonchalantly steering their scooters into oncoming traffic.

Traffic in Bangkok is predictably bad. Often the best way to get around is on a tuktuk, or motorcycle taxi, if only because they can sometimes weave between the cars and buses. In an effort to alleviate traffic, Bangkok has built up miles and miles of giant cement overpasses. Huge, eight-lane freeways act as arteries into the city. Rush hour is so bad, they actually change the direction of travel on these freeways throughout the day! In the morning, lighted signs indicate that most of those eight lanes are one-way streets into the city. In the evening, they flip them around so that there are more avenues out to the suburbs. I have no idea what you’re supposed to do if you’re driving down a lane when it switches!

Our first hotel, the Amari Atrium, was like most other large businesses in Bangkok and had hired a man with an orange safety vest to stand at the end of the driveway. His job was to step out into the street with one of those lighted, handheld, airport-runway batons, blow his whistle, and stop traffic for anyone needing to leave the hotel. Otherwise, you’d never get out.

Scooter Culture

Outside Bangkok, scooters rule the road. There are thousands of small-engine motorbikes in Thailand and a culture has sprung up around them.

Lots of people conduct their businesses from motorcycles. We saw all manner of creative examples (like the cable company motorcycle with a 12-foot bamboo ladder strapped to the sidecar), but by far the most popular were the food carts. At first glance, they could be a simple tin shack or canvas tent with a kitchen-counter-top flat area, complete with charcoal grill for cooking or displaying whatever they had to sell. Above their heads might be some shelving or a sign with the business name. Look closely, though, and you’d invariably find the whole thing was welded onto a scooter. They’d simply drive up to a curb for the dinner rush, then drive back home after selling off a few hundred kabobs or pancakes.

Most gas stations in Thailand are small mom-and-pop businesses and they can be found on practically every street corner. A “big” enterprise might be two fifty-gallon drums hooked up to a manual pump. The gasoline is pumped up into a clear cylinder so that you can measure the amount before it’s drained into your gas tank. Seeing them in operation, with the Mountain Dew-yellow tinge to the liquid, reminded me how infrequently you actually see gasoline in the States.

With a scooter, sometimes all you need is a single liter of petrol. Most of the smaller “gas stations” were nothing more than a set of shelves propped up outside a convenience store or someone’s house. Rows of 1-liter glass bottles line the shelves with a big, bold price printed above: “Gasoline! 40 baht!” Driving by, you could almost be forgiven for thinking they were Corona ads.

Highways

With all the differences, I found it surprising that the highways in Thailand were like their counterparts in the United States. The roads were in good repair, making it possible to keep speeds up. Sometimes there were toll booths along the way. Some big gas stations along the way had restaurants, convenience stores, and even separate (free!) public bathroom structures.

But just when you begin to marvel at how things are like you remember them, all the little differences remind you that you’re still in a foreign country. The “gas” that’s being pumped into the tanks is actually natural gas. They have a vacuum seal on the nozzle for safety, but even so, it’s against regulations for you to stay in the vehicle while they refuel. Our minivan driver, more often than not, wandered around the convenience store and bathrooms with the rest of us while we waited. When the station attendant was finished, he would jump in and move the driver’s van out of the way for the next vehicle in line. I can’t imagine people in the States being comfortable with that.

Hotels

I guess because tourists tend to leave the air conditioner running when they leave their rooms, most hotels in Thailand have little credit card-like slots next to the light switch by the door. Usually you get a card (or thick slab of plastic) attached to your key ring and the first thing you do when you open your door is slide that card into the slot. Otherwise, no electricity.

We went on to see these in practically every hotel and hostel in Southeast Asia. I guess saving money on electricity is very important in those countries.

I get why they do it, but it’s still annoying. I’m the kind of guy that always turns off the lights. If we’re going out all day, I’m okay turning off the AC, too, but when you need to head out into the heat of the day for just a half hour? It’s nice to come back to a cool room.

There were also times I wanted to leave my computer on (to upload photos, for instance), but 10 seconds after you remove the key ring, all power to the room is cut off. It was frustrating enough at times that we started to experiment by putting other things into the slot. Who would have thought a Costco membership card would be useful in Thailand?

Franchises

If you ever look around your neighborhood and think, “Where have all the 7-Elevens gone?” well, the answer is Thailand. There are 7-Eleven franchises everywhere. Like the joke about finding competing Starbucks directly across the street from each other, we routinely saw 7-Elevens placed the same way.

I was surprised, too, to see the franchise image is mostly unchanged over there. Big selling points were hot dogs, Slurpees, and cheap morning coffee. Many drinks were spread among half a dozen different cooler cases (including beer and wine.) About the only thing that was really different, I’d say, is that they devoted one whole aisle just to Ramen and Cup o’ Noodles.

Oh, and all the chip flavors were like “Spicy Crab Seaweed.” That ain’t American.

(In fact, I just learned 7-Eleven isn’t American, either! In 1991, a Japanese corporation took a controlling interest in the franchise.)

Also, besides the ever-present McDonald’s, KFC, and Subway, Thailand also has a bunch of Sizzlers (of all things!)

Copy Culture

This idea, which I’m calling “copy culture” for now, isn’t specific to Thailand. The idea has been percolating in my head for awhile now and it just started to coalesce while we were there.

In Chiang Mai, a vendor set up shop in the Sunday market. A sign above their cart proclaimed “ONLY banana wrap in Sunday market! Accept no imitations!” There was an air of desperation about it, as though the proprietor were saying, “I had the idea first! It’s not fair! That other guy stole my recipe!”

Let me paint you another picture, before I get to my point: Walking down the street in Patong, we came across a store selling paintings. Obviously, this was an “artist-in-residence” or “artist-as-owner” sort of place, not an art gallery. There were large, frameless canvases covering every vertical surface. The usual Thai themes of sunsets, palm trees, and tigers were represented, but the piece that catches the eye is a painting of Heath Ledger, as the Joker, with his head out the driver’s side window of a speeding police car. It was a scene from The Dark Knight.

Okay, nothing too weird about that. It was a competent painting; someone might buy it. Heath’s former agent, perhaps. We continued on down the sidewalk.

The next store was also a painting shop. And the next, and the next, and the next. All the way down the block, small stores filled with dozens of paintings.

You want to know what every single one of them had? A painting of Heath Ledger, as the Joker, driving a police car with his head out the window.

It’s like one guy got tired of painting tigers and decided to work on a passion project… and it sold! All his jealous artist competitors said, “Well, I can do that!” So they all paused their DVD players in the same place and got to work.

You see the same thing with trinket and souvenir vendors all over the world. How many stalls sell the exact same crap as the one right next to them? Why is it that every tagua nut store has the same few animal carvings? How is it that the exact same pottery can be found for sale all over East Africa? It’s because someone became successful and everyone else is trying to recapture the magic.

Two things about the painting shop tableau jump out at me.

Firstly, entrepreneurship. I remember a professor once gave our business class a scenario to think about. “Let’s say a guy opens up a hot dog stand on in the middle of a long stretch of beach,” he began. “He’s immediately successful, and you decide there’s room for some healthy competition. Where do you set up your hot dog stand?”

He gave us a minute to think about it. “Place it at either end of the beach,” most of us thought. “But which end?”

Neither, it turns out. We should have set up our shop exactly adjacent to his hot dog stand. Why? Let’s say you set up at the far end of the beach, thinking you’ll get half the beach’s business, right? Well, not exactly. Take the case of the hungry customer that’s in the exact mid-point between both hot dog stands. He should be the only indecisive customer, as he has to walk the same distance in either direction to buy himself a dog. Theoretically, everyone on one side of him will come to your shop – because it’s closer – but everyone on the other side of him will go to your competitor, because his shop is closer.

Better to set up shop right next to original hot dog stand. That way, at least everyone on one side of the beach will encounter your stand first.

Is that why developing nations always have a “shoe street,” a “muffler street,” and a “gallery street?” At first blush, it seems like sound reasoning. If you set up shop next to your competitor, you could capture half his business. But what happens when there are seven competitors in the same location? Shouldn’t you then think of moving across town, capturing that whole market for yourself?

While we’re still on the subject of entrepreneurship… In the U.S., we’re taught that we can make a name for ourselves – get rich, climb the social ladder! – if only we can come up with the next great idea. Maybe we can invent that one niche product that no one else has thought of, yet everyone needs. The ShamWow, the Snuggie. Red Bull or Twitter. If our ideas are unique and we’re the first ones to market, we’ve got it made!

I don’t think most American’s first reaction to someone else’s success is to copy it for themselves. I think our first reaction is more along the lines of, “Why didn’t I think of that? Oh, well. Back to the drawing board.” It seems to me that perhaps the Thai attitude is more along the lines of, “I’m pretty sure I can do that better than he can.”

Which brings us to the second thought I had: Copyright.

The U.S. has some of the most stringent copyright laws in the world. We value our intellectual property so much that we have made the unauthorized duplication of digital media a criminal act. How much of an impact – good or bad – has copyright law had on our businesses?

- People don’t make a living selling bootleg DVDs and software in the U.S. It’s big business in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia.

- People don’t sell paintings of scenes from movies (at least not on a large scale), lest they be sued into financial oblivion. Artists don’t have to worry about that in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia.

- Artists and inventors in the U.S. set their sights on patenting and securing their ideas, to ensure a lifetime of royalty payments. I wonder if Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia even have patent offices.

Personally, I think some aspects of our copyright system are hopelessly broken. I respect the idea that artists and businessmen should be able to control their intellectual works; in fact, I think the protections we afford them are vital to their ability to profit from it. That banana-wrap vendor in Chiang Mai: What legal recourse did he have? None.

On the other hand, I disagree that Disney should be able to sue someone 70 years down the road for using one of their cartoons in a Youtube video. Or that shadow corporations should be able to buy up software patents and make a killing suing Silicon Valley startups out of business.

But does that mean the developing world has the right of it? No, I don’t think so. I don’t know how a society pulls itself up out of the “copy culture” mentality and replaces it with a rule- and regulation-heavy entrepreneurial culture, but that might just be one of the (many) things that has to change in order for it to become a first world nation.