Old Arbat

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (23.6MB)

On our last day in Moscow – but still three days from home, because, you know, Moscow is, like, on the other side of the planet – Oksana and I returned to Arbat to have our portraits painted.

On our last day in Moscow – but still three days from home, because, you know, Moscow is, like, on the other side of the planet – Oksana and I returned to Arbat to have our portraits painted.

Earlier on the trip we had walked the length of both streets known as Arbat – Old and New. New Arbat was a four-lane highway bordered by loud neon, bright casinos, and TGI Friday’s. Old Arbat was pleasantly pedestrian with souvenir stalls, outdoor restaurants, musicians with hat-pushing assistants, and dozens of portrait and caricature artists. It was these artists’ work, photo-realistic and painted while you wait, that captured my attention and imagination.

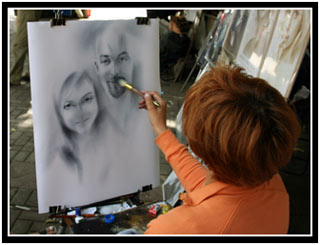

While Oksana put her Russian to good use comparison shopping for prices, I wandered among the painters. I stopped behind one woman who was painting a portrait of a young boy. To my eye, the monochrome image was almost photorealistic. Watching her perfectly recreate his eyes, I decided that if the price was right, she would be the one to paint us.

It seemed as though most of the artists on Arbat had agreed to set their prices uniformly: 700 rubles for one person, 1500 for two; doubled again for color. You could either leave a favorite photograph and pick up your portrait later, or sit still for an hour while they painted from the source. It seemed incredible to me that anyone could paint so well, so quickly, but on this street in Moscow, that particular talent was in abundance.

Oksana’s cousin, Vanya, was with us that day and because he was planning to wait around with us, I convinced her to ask our painter if it would be alright if we videotaped her process. I could tell that our selected artist, Lena, thought it a rather strange request, but she was polite enough to rearrange her easel for the camera, anyway. I set the camera on the ground, against a wall and out of the way of Arbat’s foot traffic, and started recording in LP mode.

We sat down and began our suspenseful hour-and-a-half wait.

(Don’t want to wade through more prose? Here’s a link straight to the video.)

Oksana, perhaps because she was, you know, able to understand what Lena was saying, had a completely different experience from mine. She was relaxed, slouched, and often smiling and looking around. I, not knowing any better, sat ramrod straight and stared back into the artist’s eyes. I thought that’s what you’re supposed to do when you’re posing; otherwise, wouldn’t the artist’s rendering of your eyes have them gazing off into space? Looking back, she probably found my intense stare a bit disconcerting. That makes sense, because I felt disconcerted doing it, too.

Later, while she was working on Oksana’s portion of the portrait and I was, even then, sitting imperiously still on my backless folding stool, Lena told her that she should tell me that I could relax. With relief, I let out the breath I was unconsciously holding and let a curve introduce itself to my spine.

While we sat there, Vanya kept an eye on our video camera and roamed around us taking pictures of the scene. Oksana and I were both curious to see the final results. Vanya, of course, watched the whole process unfold and kept telling us how well it was going. Other tourists stopped by to look over Lena’s shoulder and gave us big thumbs-up signs. (One Japanese guy laughed and said I looked like Lenin – another passerby was reminded of Andre Agassi.) All the while, the most interesting thing for me was looking at Lena, herself.

She painted the entire picture with a black, oil-based paint (with the exception of the glint in our eyes – she used a completely ordinary bottle of White-Out for that!), and she used such a light touch that it was essentially dry as soon as it was off the brush. She kept a roll of toilet paper nearby and frequently rubbed the whole thing over sections of the painting to smoothly blur the image. And, even though it discomfited me to do so, I was captivated by her face. When looking at the painting she was impassive, but whenever she looked up at us for reference, her eyes squinted almost shut and the corners of her mouth turned up in an unconscious smile. It was quick and repetitive and it was charmingly cute.

After giving me time to relax a bit, she came back to work on my half of the portrait. Speaking to Oksana, but more for my benefit, she said, “I need to work on his eyes; make them happier. A little less ‘Lenin.’” We laughed, but the comment made me realize how unnecessarily serious I was taking the process. We weren’t Peter and Catherine the Great, posing with our scepters and crown jewels over days and weeks (though it felt sort of cool in that posing-for-prosperity kind of way.) From then on, I tried to keep a permanent half-smile in place. My wife didn’t pay $60 for a portrait of herself with Lenin.

The camcorder’s battery died an hour and ten minutes into the process, but by then we were almost done. Oksana sneaked a couple peeks at the work in progress, but by virture of sitting farther away, I managed to restrain myself until it was done. I was excited – if it looked anything like her previous client’s portrait, it would be an amazing likeness.

Finally, she told us that we could get up and take a look. Both Oksana and I had the same initial reaction; it was good, but not great. There was something slightly off – my likeness was too angular, Oksana’s thought hers was a little elongated. Of course, we didn’t say anything at the time. Besides, it wasn’t as if we weren’t satisfied; we were. We just weren’t blown away; probably because our expectations had been so high.

While Lena rolled the painting into a tube and wrapped it in newspaper, Oksana dug out her rubles. Just before leaving, almost as an afterthought, we asked Lena if she had an e-mail address. I promised to send her a copy of our time-lapse video once we returned to the States.

Since leaving Arbat, our view of the portrait has changed for the better. While we feel that the painting doesn’t quite measure up to reality in certain ways, we’ve noticed that others don’t necessarily notice the differences. It’s probably because we see ourselves in the mirror every day and any imperfection is likely to stand out. At any rate, it makes for a cool story, a great memento, and a fun video: