Review of Michael Crichton’s Travels

You know what sucks? Walking into one of the best bookstores on the planet and realizing that you can’t buy any books.

That’s how I found myself back in July, when we were passing through Portland. We had a couple hours to kill and I wanted to spend it in Powell’s. The only problem was that Oksana and I had just reduced our material possessions down to what could fit in our backpacks, and even if I could spare the time for some recreational reading, I couldn’t rationalize the added weight of a single paperback. Not to mention the iPad we’d brought along. If there’s one good argument for digital publishing, it’s that it is tailor-made for travel reading…

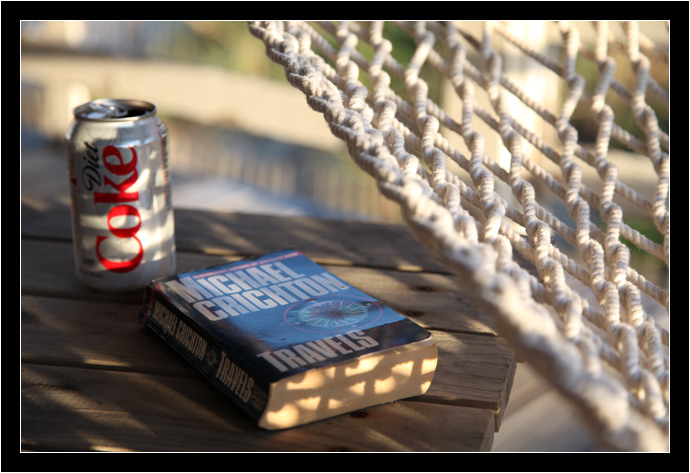

So I found myself window shopping the bookcases, glancing over the collections of some of my favorite authors, when I came across the Michael Crichton section. Sphere, Jurassic Park, Andromeda Strain. Good reads, good times. But wait, what’s this? Travels? I picked up the worn paperback and read the back cover. How could I have read practically everything Crichton has written and not known that he wrote a book about traveling? Seemed like an omen. Screw iBooks. I had to buy this.

“Writing is how you make the experience your own, how you explore what it means to you, how you come to possess it, and ultimately release it.” –Michael Crichton

I’m not in the habit of collecting quotes, but this one, about why Crichton tackled a book on his physical and spiritual travels, so perfectly explains why I write that I couldn’t help but write it down.

I didn’t get a chance to read it until we got to the beach in North Carolina. It’s no wonder I’d never heard of Travels. Not only is it a book wholly different from its marketing, it doesn’t paint Mr. Crichton in a very good light (even though it’s his own memoir.)

One thing I liked about Crichton was the way he obsessively researched his books. After reading a few of them, you couldn’t help but see how he comes by his ideas. Some new scientific headline would tickle his interest – say, gene splicing (Jurassic Park), nanotechnology (Prey) or virtual reality (Disclosure) – and off he would go, reading anything and everything even vaguely related to the subject. Eventually, some ideas would coalesce into a plot, setting, characters… and he’d spin us a yarn.

Jurassic Park is a perfect example. Gene splicing across species wasn’t anything new to write fiction about, but when he paired it with the 65-million-year-old mosquito-in-amber trick to get it to work with dinosaurs, it turned into a great idea. I imagine the same story would have been created by any number of other authors after that T. Rex bone was broken and scientists discovered soft tissue preserved inside, but because Crichton was already up to his eyeballs in splicing research, I’m sure the idea popped into his head as soon the first amber story crossed his desk.

Anyway, back to Travels.

Expecting the book to be about his travels around the world, I was initially caught off guard when the first 100 or so pages focused solely on his struggles through medical school. It was interesting, however, in a Stephen King On Writing sort of way, but it was also an awful lot of setup to get to his actual travels.

Once I finally got to the travels themselves, I realized that the vast majority of them were not about travels in our world, but rather spiritual travels through his mind. I have nothing against Crichton for wanting to write about how he spent his life fighting against his medical and scientific education by exploring the paranormal, but when I picked up a book with a globe and compass on the cover, I didn’t expect such a large portion of it to be about astral projection, past life experiences, fortune telling, and talking cacti. Yes, really. He has a conversation with a cactus.

The sections he did write on travel were fascinating, however. I enjoyed reading about the culture shock of living in Bangkok, diving among sharks, hiking with a family of mountain gorillas, dodging bandits along the Karakorum Highway, and his hike up Kilimanjaro (especially since I’d climbed a mountain of similar height, Cotopaxi.)

You could see how some of the travels directly influenced his work. One of the only things I remember from the Congo movie was a funny, tension-releasing moment when Dylan Walsh’s character is charged by a silverback gorilla. His guide had told him, “no matter what, don’t run,” and he somehow manages to stand his ground. When the gorilla finally backed down, Walsh looked behind him and everyone else in his group had fled.

In Rwanda, something very similar happened to Crichton, too. Write what you know, eh?

There isn’t much the aspiring travel writer can take away from Crichton’s work here. The travel industry changed significantly since the 70s when he did the bulk of his travel. And while it was interesting to read about how he was able to visit extremely remote areas of the world, he often did so, presumably, by shoveling out a ton of Hollywood money. Every time he mentioned a caravan, his full-time guide, an armed guard, or even just his travel agent, I thought, “Well, we won’t be doing that!”

But the biggest problem I had with the book was Crichton’s exploration of the paranormal. Since this turned out to be the thesis of Travels, that’s not a small complaint.

Again, he dove into his research. Mostly, he chose his travel locations to further his understanding of spiritualism, heightened consciousness, and the like. Whole chapters are devoted psychic retreats in California, training with “trance mediumship” gurus, and learning to read his fortune by tarot card.

It’s not that I’m not interested in his opinion on these subjects. In fact, his conclusions are the best reasoned arguments I’ve read for the existence of the paranormal. What bothers me is that the summary on the back of the book barely hints at his thesis and only after finishing the book can I see that the marketing copy was picking its words carefully, intentionally aiming for the ambiguous.

I suspect they had to market this book this way, as most of us think of Crichton as a very serious, scientifically-minded author. It must have been tough selling an autobiography that paints a popular author, in many people’s minds, as a kook.

I put this book down with a completely different impression of the man that wrote it. Before, I thought of Crichton as a medical-doctor-turned-author with a voracious appetite for learning. But after he laid bare his desire to find within himself a link to unconscious powers, I couldn’t help but lose a little respect for him.

Still, it paints the portrait of a complex, interesting man. I’m saddened that Crichton recently lost a fight against cancer. Despite not really liking Travels all that much, of all his works, this book made me want to meet him more than any other.

Nice, review. I understood exactly what you meant when I read it. I would also add that he used a lot of exaggeration (like when he climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro.)

Hi, Jeffrey. Glad you liked the review.

I’m very curious about the Kilimanjaro exaggeration, though. Have you climbed it? If so, I’d love to hear how your experience differed from Crichton’s telling.

We were in Tanzania last year and one of my big regrets is that we didn’t try the climb (too spendy.)