Thoughts on Russia

The first time I traveled to Russia was in 2006. Oksana and I split our time between Moscow and St. Petersburg, because while she is originally from Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy in the Far East, her family happened to be spending time in the big city. Her brother, Andrey, played host and seemed to have an all-day itinerary planned for us every day we were there. We were exhausted by the end of our “vacation,” but looking back through our photos, I’m amazed at all the things we got to see and do in just three weeks.

I always felt guilty for not writing much about our first trip through Russia. Even way back then, I had a mental list of things to write about for one of these “Thoughts On” blog entries. When we crossed the border into Russia again last September, my notes were already full of half-remembered items that I jotted down on the bus from Estonia.

Russia

Asking “What is Russia like?” is like asking “What is the United States of America like?” How do you answer that? When a country spans most of a continent, has citizens from every socioeconomic background, as well as a history dating back thousands of years, you can’t just sum it up in one or two sentences.

I’ve seen two of the biggest, most prestigious cities in Russia, a couple larger cities in the east, and passed through many a rural town on the rail line between St. Petersburg and Irkutsk. About the only thing I know for sure is that Russia isn’t easily summed up.

I can tell you, however, that there’s a strange dichotomy when Russians think about their own country. On the one hand, there’s the feeling that Russia is the greatest country on the planet. Mention that you’ve been to the world’s largest lake and they’ll tell you that Russia has the world’s deepest. Describe to them how something is done in the States and they’ll explain to you why the Russian method is better.

Then there’s the flip side. A Russian who has traveled outside their country can’t help but see how bad their own roads are upon returning. Engage them in conversations about why their tax dollars aren’t being used to repair said roads and they’ll complain bitterly about how the high level politicians are pocketing billions of dollars and what money is level over is being funneled by the government into Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Even as they complain about how bad things can get in Russia, though, they manage to maintain a sense of “Only in Russia” pride. After an eight-hour day spent driving less than 30 kph on truly horrible roads, Oksana’s brother said to me, “Now you can say you’ve seen real Russian roads!” I wasn’t impressed, but then I hadn’t applied for my tourist visa in the hopes of seeing spectacular potholes.

Later, there was a strikingly similar incident when we pulled into a parking lot behind an old concrete apartment building. “Now this is the real Russia,” he said in almost the exact same way. “This building hasn’t had maintenance done on it since the day it was built!” It didn’t seem like I was supposed to be impressed because it was still standing. It was more of a “Can you believe what we have to put up with?” vibe.

I think this patriotic feeling of superiority come from Soviet times, when Russia was a superpower vying for a lead role on the world stage. Even then, living in Russia wasn’t necessarily better than living in any other country, but the Soviet propaganda was intense and citizens were told daily that their country was the best in the world.

I don’t mean that to sound derogatory, either. We Americans suffered through the same media-delivered, government-sanctioned news during the Cold War. Most every American growing up from the 40s onward probably still thinks the U.S. of A. is the greatest country on the planet, too. And now, with the political divide between the left and right so wide, as well as congressional approval ratings at a 235-year low, I think it’s safe to say that we Americans have the very same love/hate relationship with our own country.

Women

I have a theory that there are only two types of women in Russia. Supermodels and babushkas. Walking the streets of Moscow, that’s all you ever seem to see. We were there during a heat wave and all the teens-to-twenty-somethings were dressed in the skimpiest of clothing, showing off their long limbs and rail-thin frames. Older, matronly types often sported the thick, square bodies I associate with Russian grandmothers. All they’d need to complete the look is a thick shawl over their shoulders and a bandana tied down over their hair. Some actually had them.

Of course, the women of Russia come in every shape and size, but much like a nation with a tiny middle class, the extremes get all the attention. I found myself wondering why the younger women were generally so thin, while the older women so stocky. Is the courting process so competitive that women have to look like supermodels in order to attract a mate? (Maybe! Wikipedia says the ratio of males to females is .86/1. That’s a huge disparity.) Once married, do they quit the fight and let their waistlines go? Does the butterfly spin a cocoon and emerge a fat caterpillar?

Another thing I learned while studying these supermodel types (yes, studying! But I’ll have you know that my wife was the one pointing out the best examples!) was that “thin” does not necessarily mean “fit,” or even “healthy.” Seems obvious to me now, but I think that my impression of body types has been affected by living in the States. More often than not, when an American woman is that thin, she got that way by working hard at the gym. “Thin,” in the case of Ms. America, usually comes with strength and some obvious muscle tone, which, if we’re being honest here, I find more attractive than heroin chic (no surprise, considering that I’m talking about my cultural norms here.) I have the sad suspicion that much of the thinness in Russia comes from anorexic and/or bulimic tendencies.

You can also see many – many! – examples of plastic surgery on the streets of Moscow. Enhanced breasts, Botoxed foreheads, duck lips. “Beauty” can be bought, apparently, in the motherland.

We worry about how fashion supermodels and Photoshopped celebrities on magazine covers are making young women in American dangerously image conscious. If you want to see that taken to its logical extreme, I’ll bet you can find it on the Moscow nightclub scene.

Semi-Unisex Bathrooms

I noticed a few public bathrooms that were almost, but not quite, unisex. They shared a common washing area with sinks and mirrors, but the men and women went into different attached rooms to find the toilet stalls.

Not a big deal, really, and also a pretty good space-saving idea. Still, I bet it screws with certain social dynamics. I doubt the women hang out and gossip while putting on their makeup if any old guy can eavesdrop while standing in front of the urinal.

Smiling

Oksana and I have a running joke when we take part in her family photos. “Wait!” I say to her. “Is this photo going to be Russian- or American-style?” Meaning: “Do we smile or look deadly serious?”

Having been with Oksana over 10 years now, it’s nothing new to me. Russians just don’t smile when posing for photos, whereas in the US, we’re trained to say “cheese” because the word tugs up the corners of our mouths and we can maintain the last syllable for as long as we need to smile.

When I met new family members in Irkutsk this time around, I was momentarily taken aback by how friendly they all seemed. Big hugs, kisses on both cheeks, and excited ramblings I didn’t understand but ones which Oksana was happy to translate. Why is this so surprising? I wondered. Then it hit me: These were the people I’d seen countless times in photos and I’d unconsciously formed an opinion about them based solely on the way they gazed, stern and stiff-backed, into the camera lens.

It only takes one walk in a major metropolitan area to realize that Russians don’t casually smile at strangers on the street, either. I have a distinctly American habit of unconsciously nodded my head or smiling at someone when I make eye contact. In Russia, I never got anything back.

When Oksana’s brother visited us last year in the States, he noticed the difference, too. Why was everyone smiling at him? We talked over our differences in expectations and each learned something new about the other’s culture. For example, he learned that Americans are courteous to strangers while I learned that when an American smiles at someone on the streets of Moscow, the Russian is most likely thinking, “Who let the village idiot wander free?”

Heating

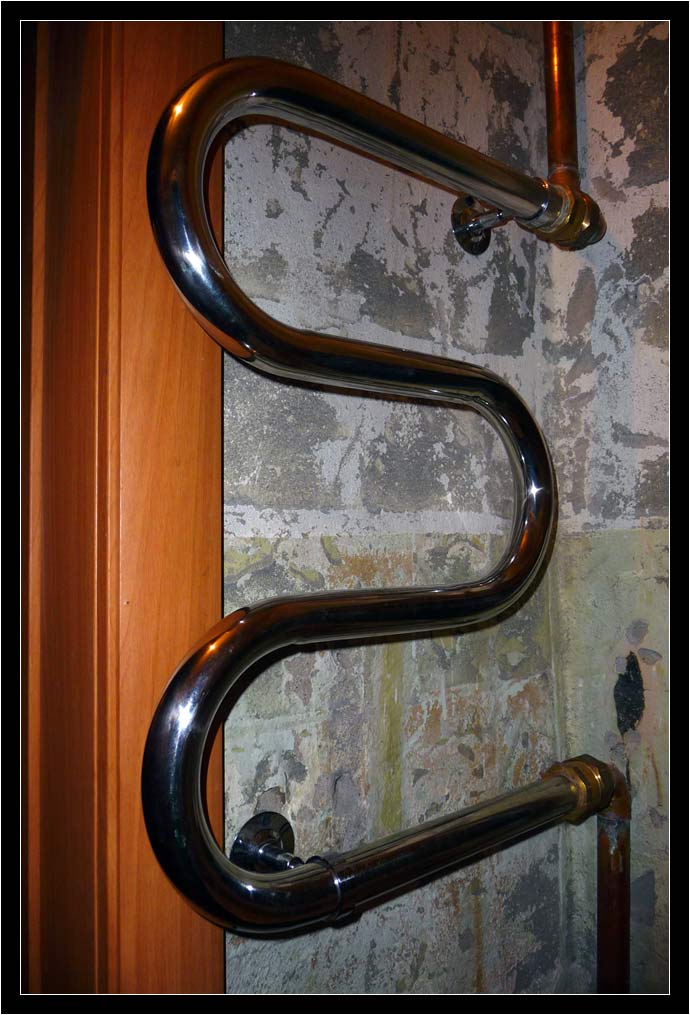

Many (most?) people in Russia heat their homes with hot water. That, in itself, isn’t all that special; it’s how they do it that intrigued me.

In the cities, it’s the municipality that supplies the hot water. There’s a huge network of giant pipes that move the water all over the city. It’s a closed circuit that eventually leads back to a steam plant – a huge factory that does nothing more than heat water and force it into the system.

The pipes enter practically every building within the city limits and the heat from uninsulated pipes (radiators) is what keeps everyone’s living space toasty warm throughout some extremely cold winters. A side benefit is that they never have to wait for the water to warm up in their showers!

There are, of course, some problems with a system such as this. In the warmer summer months, they often take the system offline for repairs, meaning people have to have backup hot water tanks if they want warm showers. Also, there are outages – a broken pipe somewhere in the city or, God forbid, a steam explosion at the plant, can take out the whole system. I can’t imagine how dangerous something like that could be to the population in the dead of winter (I suppose no more than an extended power outage in Alaska.) Not only does a shutdown put the primary method of heating for most people at risk, if it’s not quickly fixed, the whole citywide network of pipes could conceivably freeze and burst.

Shoes

You know how some people in the States ask you to remove your shoes when you come into their homes? Maybe it’s just the circles I frequented when growing up, but I always thought that was the exception to the norm. Not in Russia. Everyone takes off their shoes when they enter a home.

When we take off our shoes in the States, it’s usually perfectly acceptable to walk around the house wearing socks. (If not, no one has ever said anything to me about it!) In Russia, that’s not normal. There’s always an extra pair of slippers by the door for visitors.

Personally, I never took them up on their offer – seems weird to me to put my feet into a shoe that other people have worn. Oksana cautioned me that my socks would end up getting dirty, but that’s why we wear socks, right? So our feet don’t get dirty?

The slippers-for-guests thing in Russia must be deeply ingrained. In the airport security line, they have to remove their shoes and send them through the x-ray machine, just like we do. However, people are not expected to walk through the body scanner in their socks. Right by the belt is a huge barrel full of disposable elastic booties for the 10 steps it takes to get to the other side.

Once again, I opted not to wear them. If everyone was wearing booties, I figured that stretch of carpet was the cleanest section of floor in the airport!

Alcohol

All those rumors and stereotypes about how much Russians like to drink? Totally true.

I can remember the first meal I shared with Oksana’s family, when they came to Juneau for our wedding. Her father poured each of us a shot of vodka to toast our union. I hardly drank at all back then, but I thought it would be impolite to refuse. We had a second round to toast… I don’t know what. Their safe flight to the States? I cut myself off after the third shot, when we toasted the freshness of the salad.

I can’t keep up and I don’t even try.

Once, when we were out on the town in St. Petersburg, our friend, Andrey, kept refilling my drink after I’d already achieved a more-than-sufficient buzz. We were talking iPhones and travel apps, so I decided to show him the Translate part of the Google app. (Not to go too far off topic, but have you played with this app yet? We’re this close to having Star Trek universal translators, people!) I hit the microphone button, spoke into the phone like I was making a normal call: “Please, no more drinks. I’m already drunk!” I checked to make sure that the voice-to-text recognition worked (it did, perfectly) and hit the translate button. A second or two later, the text changed to Cyrillic, so I hit the speaker button and a computery monotone spoke the Russian words out loud. He laughed, and I was off the hook, drinking-wise, for the rest of the night.

Over the years, Oksana’s brother has scaled back his drinking offers, but I enjoyed having evening meals with him at his home in Kamchatka this time. Rather than vodka, he’s more interested in cognacs and he was eager to show off the local beers, too. I just wish we’d visited shortly after our stay in Argentina. With all the wine we consumed there, my alcohol tolerance had been at an all-time high!

Another obvious difference between Russia and the U.S. on the drinking front is how often you see people who are completely wasted walking down the street. I’m used to seeing falling-down drunks when the bars close back home, but you can spot them any time after sunset on a Friday or Saturday in Russia. The drinking age is lower in Russia; that probably has something to do with it. There’s nothing stopping kids right out of high school from drinking past their limits. Also, no open container laws. It’s perfectly acceptable to stroll down the street with a big ol’ forty or a bottle of vodka.

I shudder to think what the drunk-driving accident statistics are like. On that front, at least, it sounds like they have zero tolerance laws in place. If you’re pulled over with any alcohol in your system, you’re busted. No leeway like we have with a .08 blood-alcohol or anything. If the breathalyzer registers anything, your license is automatically suspended.

Finally, one last note on alcohol in Russia: They sell beer in plastic bottles. We can debate the merits of aluminum cans vs. glass bottles, but plastic? That’s just wrong.

Water

Oksana and I have gotten used to bottled water. We’ve done so much traveling that we can’t keep up with which cities do and don’t have safe drinking water. I did notice that many homes in Russia had two faucets built into the kitchen sink, though. The skinny one with the thin stream was for drinking, while the big one was for washing dishes and the like.

Wonder if that has something to do with the endlessly-recycled hot water system?

Bread

Russian like their rye bread. While staying with Oksana’s family, we went to get a new loaf every other day or so. Meals always had a stack of sliced bread sitting nearby to go with just about anything: Soup, pasta…maybe even more bread.

Admittedly, this could just be an Oksana-family quirk, but I noticed that for most meals, many items were just spread out on the table and you were expected to grab what you wanted, sort of “tapas style.” Breakfast usually had two or three different kinds of cold-cut meats or salamis, cheeses, bread (of course), and yogurt or cottage cheese. Also, the idea of using two pieces of bread for a sandwich is foreign over there. They like theirs open-faced.

Platonic Tomatoes

I’ve seen a lot of good tomatoes in my life – at the supermarket, growing in my grandfather’s garden – but none like they had for sale on the street next to a random metro exit in the middle of Moscow. A taut skin, with an even Pantone 199 Red, stretched almost to the size of a grapefruit and perfectly round. The flesh parted for a sharp knife with no loss of juice and the taste… the taste was so sweet! You know that old debate on whether tomatoes are fruits or vegetables? When you bite into one of Russia’s finest, you’ll know that they’re a fruit. You’ll want to eat them like apples!

We picked the perfect time to visit Kamchatka, too, as her brother was busy harvesting all the ripening vegetables from his giant greenhouse. Every night we devoured a huge bowl of salad, made from fresh tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers pulled from the garden that afternoon.

In fact, this is a staple of Russian life. It seems like everyone from the lower-middle class on up has a summer home, or dacha, where they retreat from the city during the hotter summer months and grow endless amounts of fruit, vegetables, and berries for a fall harvest. Anything that isn’t eaten on the spot is pickled, or jammed, or in some other way preserved for the winter. Oksana’s brother was no exception; his dacha just happened to be on the same property as his house.

Eating

While we were in Bulgaria, we stayed with one of Oksana’s friends who was living with her babushka. There were on an extended summer vacation and had fallen into a set routine. The grandmother took it upon herself to make sure there were heaps of food on the table every day at 8am, noon, and 5pm.

During our travels, Oksana and I had fallen into a routine of our own. A typical day would see us eating a large breakfast (if it was included at our hostel), skipping lunch, and then having a late dinner. Sometimes, if we slept in, we’d skip both breakfast and dinner, letting a big lunch and a snack suffice. Come to think of it, our eating “routine” was probably not having a routine.

At any rate, three big meals a day were more than we could handle, especially considering how we were being fed. It took me a while to realize that Babushka made multiple courses for each meal. She would leave the second simmering on the stove. I’d load my plate up with all the food on the table and eat my fill… but the second my plate was clear, Babushka would be up and filling it again with the main course. And naturally, I had to be polite…

Americans and Russian families both seem to a “you have to eat” mentality, but they’re different in execution. Parents pile American kids’ plates high and demand they “clean their plate.” In Russia, there may not be as much food on the plate initially, but it will always be refilled.

Superstitions

Living with a Russian, I’ve learned a few new superstitions. Never kiss in a doorway. Before leaving home on a trip, take a moment to sit down on the couch. If you have to return because you forgot something, be sure to catch a glimpse of yourself in a mirror.

I totally don’t understand any of those.

I learned a few others while we were visiting this time around, mostly having to do with “cold.” Don’t drink cold liquids before going to bed. Don’t sit on a cold floor. Always wear slippers indoors; don’t ever let your feet get cold or wet.

Also, it’s unlucky to pass a funeral procession.

It makes all sorts of sense that Russians would worry about cold weather. We all know what Siberia can be like in the winter and superstitions are, at heart, there to warn us away from things that might do us harm. It’s bad luck to walk under a ladder… because there’s probably someone working on it and they could drop a bucket on your head. It’s bad luck to open an umbrella indoors… because you’re more likely to put someone’s eye out or knock over a lamp. It’s bad luck if a black cat crosses your path… because, well hell, I have no idea.

Oksana and I discussed all the Russian cold-superstitions we could think of and we eventually agreed that they’re not any more based on reality than the black cat thing. You can’t get a urinary tract infection from sitting on a cold floor, anymore than you can come down with a cold from going outside without your coat on, getting your feet wet, or having a glass of water before bed.

But still. When you consider that these superstitions were probably created hundreds of years ago, long before modern medicine established that sickness is caused by viruses and bacteria, you can take them for what they are: Common sense and cautionary advice.

I still don’t know why I can’t kiss my wife in a doorway, though.

Tea Culture

Russia is big on tea. And not the bag-with-the-dangly-string kind we’re used to seeing in the States. More often than not, they brew the real stuff, dried tea leaves of all different kinds, and filter them out in the teapot as they pour. You can plan on having hot tea for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Or rather, I should say, you should plan to have tea after breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Russians rarely have anything to drink while eating their meals. They save theeir tea for after and claim it aids in digestion.

More superstition? Maybe that irrational distrust of cold is why Russians drink so much hot tea. That seems right to me – you should see the way Oksana’s family looks at me when I crack open a can of Diet Coke for breakfast.

Camouflage

We toured a big chunk of the remote Kamchatka peninsula with Oksana’s brother. He took us to the hot springs, to a geothermic field with geysers, up volcanoes, to the ocean, and fishing in the rivers. We saw a lot of outdoorsmen along the way and, almost to a person (including Andrey himself!), they were dressed in camo.

I guess what surprised me was not so much that they were dressed in camouflage, but that I never saw an orange safety vest. Camo is made for blending in, which is perfect for hunting when you need to sit in a blind waiting for a deer, but it’s also dangerous. In the U.S., enough people have been shot wearing camo that it’s pretty much expected that everyone will wears orange during hunting season. Considering how many Russians drink while out in the bush, I’d cover myself in orange from head to toe. And maybe strap a pair of those disposable air-horns on my shoes, too.

I’m guessing all this camouflage-as-an-outdoor-fashion-statement comes from the military. In Russia, everyone has to put in a couple years of service when they turn 18. Even if they don’t get to keep their gear when they get out, the camouflage patterns are so familiar by then that they probably wouldn’t think of buying anything else.

Metro

What does it say about my childhood that the first real experience I had with a metro was in Moscow? (Hint: It says I grew up in small-town Alaska.) Thinking back, I guess I commuted a time or two on the Mexico City metro before we visited to Russia, but because I was mostly following other people in our group there, it didn’t leave as big an impression on me. We used the metro every day in Moscow and I quickly became familiar with it.

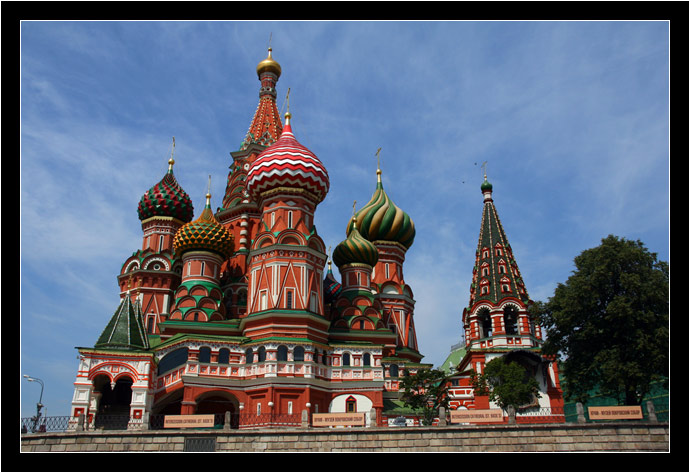

Technically, the metro system as a whole is quite impressive. Most stations are underground – the deepest is over 275 feet deep! – and long escalators are used to ferry people down to the platforms. During peak hours, the trains are never more than a few minutes apart and above every tunnel are digital readouts telling you when the next is due to arrive.

The Moscow Metro isn’t only an incredible feat of engineering and a testament to efficient management; it’s also a work of art. Each station has its own theme. You might arrive at one stop strung with old chandeliers, make a connection to another with polished marble floors, then get off at a station with walls tiled with intricate mosaics.

I could spend an entire vacation exploring the Moscow metro, just learning about and photographing the different stations. I’ve been on many more metros since our first trip to Russia, and some of them have been quite good, but none of them compare to Moscow’s.

Driving in the Far East

We’ve traveled through so many countries at this point in the trip that I’d have a genuinely hard time telling you which ones drive on the left and which ones drive on the right. It’s best for me, at this point, to simply look both ways before crossing any street, lest I be clobbered by a car driving in a lane I wasn’t expecting it to be in.

But Russians share the same side of the road with us in the U.S. The right side of the road!

Things get a little crazy once you get to Siberia, though. (In fact, things are crazy enough in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Think “Los Angeles” with less respect for the rules and more traffic jams.) Near Lake Baikal, they still drive on the right side of the road, but three out of four vehicles have their steering wheels on the right side of the car, as well. Think about that for a minute. It’s as if 75% of the population is driving U.S. Post Office delivery vehicles.

Why? Well, it’s because Siberia is surrounded by Asian car markets. Japan, Korea, China… importing from these countries is cheap, so they can have their pick, but most of the automotive manufacturers are saving their best work for the cars they drive in their home markets. They export inferior vehicles to markets where they drive on the right. When faced with an either-or decision between quality and steering wheel placement, apparently three-quarters of Russians prefer quality.

With some effort, a driver can make most of the necessary adjustments. It’s not all that hard to retrain your brain to shift gears with your left hand or to mentally swap the turn signal with the windshield wipers. You could overcome those muscle memories with an afternoon of practice. What you can’t overcome – ever! – is the fear that wells up inside you when you decide to pass another car on the road.

Think about this for a second. You’re behind a big semi; it’s going too slow on a two-lane rural road. You decide you want to pass it, so you start to inch toward the oncoming lane to see around him… but wait! You’re driving on the right side of the car, so that means you have to maneuver your whole car into the oncoming lane before you can see around the semi!

There are probably all sorts of infrastructure problems that arise when there isn’t a standardized driver’s side of the car, too. I noticed at least one. Ticket dispensers at the entrance to paid-parking lots had to be placed on both sides of the car, because they can’t be sure which window was going to be rolled down.

The roads in the Far East are terrible, too. There’s one major thoroughfare through Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy that’s in decent repair – four lanes, two in each direction – but that’s only because the president came through a few years ago and was appalled by the conditions. I guess he was able to channel some money toward PK once he returned to Moscow. While we were there in September, they were repaving some side streets and one or two roads out of town, as well, because he’s due for another visit soon.

Driving anywhere outside of the city can be pretty rough. Lots of dirt roads with huge potholes reduce your speed to almost nothing. Everyone has an SUV; it’s the only reliable way to get around. It’s not so bad when you take the time to negotiate all the bumps and holes, but even so, after three or four hours of driving on roads like that, your neck is sore and your nerves are shot. Winter’s much better. People just drive on the snow.

One last thing about the frustration of driving in PK. The main road has two lanes in each direction, but it can take forever to drive from one end of town to the other. First off, there is no bus lane, or even bus stops, so big buses are constantly blocking the right-hand lane while picking up or dropping off passengers. Second, there’s no left-hand turn lane at the stoplights, so whenever a car is waiting to turn left on a solid green, it’s also blocking one entire lane. These two events often coincide to bring everything to a standstill. If they had the same rules against excessive lane changing as they do in the States, no one would ever get anywhere at all!

How important do you think roads are in the economic development process, by the way? I got to thinking about that as we sat in a PK traffic jam for an hour or two. It seems to me that paving roads and maintaining them might be one of the best values for a country’s tax dollars. I couldn’t help but think about how much business wasn’t being done while all those cars sat bumper to bumper, not to mention how much time is wasted when you can only drive 30 KPH because everything but the main avenue has reverted back to dirt roads with lake-sized, water-filled potholes.

Driving Licenses

One day, while we were driving back from the Mutnovka geothermic field on the top of a volcano in Kamchatka, we came across a police officer on the side of the road. He had obviously pulled over another car (his patrol car was parked behind it) and its two occupants were standing with him alongside the road.

As we approached, he took a step out into the road and motioned for Oksana’s brother to pull over. After we’d stopped, he approached the driver’s side window and asked Oksana and Andrey to accompany him for a minute. I, of course, had no idea what was going on. Oksana told me to sit tight; they’d be right back.

I watched through the windshield as the officer explained something to them and then they all bent down over some papers spread over the hood of the car. Andrey and Oksana signed some stuff, got back in the car, and we drove off. “What was that all about?” I asked.

Oksana told me that the couple had been pulled over for speeding – excessively so. Because of that, the officer was issuing them a ticket, probably involving a fine or a court date or some such thing. To insure that they would show up to pay their fine, he was revoking the driver’s license. As long as they showed up and paid their fine on time, he’d get his license back. If he didn’t, the next time he was pulled over, he’d be arrested.

Oksana and Andrey were needed as witnesses. They put down their names and contact information, verifying that this cop was revoking that guy’s driver’s license. The only reason we were pulled over was because we happened to be the first car to come along.

I can’t imagine something like this working in the U.S. The only way a police officer can confiscate your I.D. is if they arrest you, and they’re not going to do that for a common speeding ticket.

Seems like this is a Russian system of checks and balances to me. A judicial workaround to combat corruption. Consider what might happen if the cop didn’t revoke the license. What would guarantee that the driver would show up at court in a society where he could bribe his way out of such proceedings? On the other hand, imagine if cops weren’t required to obtain a third party witness to the confiscation? Corrupt officers could simply take the license and demand a large bribe if the driver wanted it back.

Law and Order

I saw Law and Order: Criminal Intent on TV while we were in Russia, or rather, I saw, “Закон и порядок. Преступный умысел.” It wasn’t just a dubbed version of the American show. This was a whole new show, with Russian writers, directors, and actors.

I couldn’t understand anything that was happening, except… well, I knew when the scene changed. It had the exact same chung-chung sound effect.

Oksana never sat down and watched an episode, so I didn’t get an answer to the first question I had about the series. They presumably follow cases through the criminal and judicial system, like they do on the U.S. show, but do they address the things that are uniquely Russian or do they simply rehash plots and scenarios from the American version? For instance, do they address or gloss over the obvious corruption in the system?

That would make for some fascinating television, but I could also see how the “ripped from the headlines” feel of the Law and Order franchise could draw the wrong kind of attention from some very powerful and dangerous Russian authorities.

Language Tangent

As I was writing about Law and Order, Oksana and I were just discussing the show’s Russian name. Apparently Wikipedia calls it “Law and Order: Criminal Mind,” which is an inaccurate translation. Oksana said she could understand why someone could make that mistake, though. The Russian words for “mind” and “intent” come from the same root.

How interesting! I thought. The word they use for the thinking part of the brain is related to intent. There’s something almost poetic about that.

It got me thinking about the same words in English. We say, “mind your manners,” or “mind your parents.” What does “mind” mean when we use it as a verb? It means, “to pay attention to.” Attention. Intention? Intent!

I love puzzling out languages!

Speaking of languages, the United States always gets a bad rap because the vast majority of Americans only speak English. After traveling through 25 countries or so and seeing the majority of them with thoroughly bilingual cultures, Russia surprised me by also being almost aggressively monolingual.

Maybe it’s a superpower thing. “Our country is so big and important, we don’t need to learn how to speak your language; you need to learn to speak ours!”

Also, I don’t know why it took me so long to realize this (being married to a Russian girl these past 8 years), but Russians speak mostly with their lips.

(I think the only reason I noticed was because of all the time I spent as a fifth wheel in dinner conversations. You still look at people when they talk, even if you can’t understand what they’re saying, and I found myself observing the manner in which Oksana’s family and friends spoke.)

The way Russians speak with their mouths almost closed, made me think of some videos I’ve seen online in which people dissect accents. There’s a placement element to speaking in an accent where you “move” the voice around your mouth. Some accents sit way in the back, by the throat. Some you try to move up toward your nose. Russian, apparently, sits out on the tip of your lips.

Russians famously have a difficult time with our “th” sound, where the tongue slips through the teeth for just an instant. I wonder if every sound in the Russian language can be made with the teeth clenched shut.

American Movies

Speaking of American entertainment, I’ve noticed that Russia has a unique way of dubbing, well, everything. Normally when you dub a movie, you kill the original audio track completely and have new actors give voice to the characters in their own language. In Russia, they do use new voice actors, but they don’t remove the original audio track. This is exactly as irritating as you’d think. It sounds like two people talking at the same time, in different languages.

We sometimes see the same thing being done to news broadcasts or on the radio when someone is being interviewed in a foreign language. They begin speaking, in Spanish, say, and then the editor lowers their volume and has an interpreter come in and speak over them in English. It’s a useful trick when you want to establish that the original speaker is a foreigner. It’s completely annoying when a whole movie is needlessly done the same way.

Oksana said they’ve done it this way for as long as she can remember. Everyone accepts it; it seems like a cultural idiosyncrasy at this point. I wonder why they do it this way, though. What’s wrong with subtitles? Is it because the literacy rate is (or was) too low for most people to understand them? Can it be that Russians read slower for some reason and can’t keep up with them? Or is it simply that the Hollywood movies that were originally dubbed into Russian weren’t done with the original edits? That is to say, maybe there weren’t able to remove the original, English audio track without also removing the sound effects and music as well, so they just dubbed right over the top of it all in Russian. And then, once everyone got used to it being done this way, it just became a thing.

At any rate, Russia has its own very successful movie industry where everything is produced in Russian. I happened to catch an action movie where some American soldiers were obviously the bad guys. When those Americans spoke English, even then, they dubbed audible Russian over the top of their lines so the Russian audience would know what was being said. No subtitles at all.

Two other notes about Russian movies: Yes, Americans are always the bad guys. And now, after having seen a couple movies with Russian actors playing Americans and royally butchering the accent, I finally have sympathy for Oksana and all those times she’s listened to American actors faking their way through their Russian characters’ lines. So painful it can’t help but rip you right out of the movie!

Customer Service

I’ve told Oksana I wouldn’t mind living in Russia for a time, so that I could learn the language through immersion. She tells me that’s never going to happen; she has no interest in living there again.

It’s not the country that would bother her. It’s the business world. If we move there, she would have to get a job, and working in such a messed up system would drive her crazy.

Partly, it’s because she’s an accountant. She hates that Russian businesses keep two different books: One with the numbers to show the government for tax purposes, and one that has the real numbers related to the business. It’s an open secret; everyone does it – everyone has to do it. An honest business can’t compete in a corrupt market.

The other thing Oksana hates is the customer service – or lack thereof. This is something that has probably been improving since communism gave way to capitalism back in the 90s, but it’s still a long way from U.S. standards. No one’s going to get fired for treating customers poorly in Russia.

To be clear, it’s not just the fact that a few jilted customer leave angry after a transaction. Let’s face it – that still happens in the States all the time. The problem in Russia is at the institutional level. Problems with the way customers are handled by a business actually slow the business down.

An example: When we were at the train station in St. Petersburg, buying our tickets for the Trans-Siberian Railroad, we stood in line at the counter. While we were waiting, people would appear out of nowhere, cut to the front of the line, and the person behind the counter would stop what they were doing and service them instead of those of us who had been waiting patiently. This happened two or three times and people were getting seriously angry.

Turns out, it’s policy for employees to help customers who are purchasing tickets for the trains that are departing soonest. These people were justified in queue-hopping because they’d waited until the last possible minute to purchase their tickets. Some people gamed the system, knowing they’d never have to wait in line at all, if only they wait until the “10 minutes to departure” announcement for their train.

Logically, this makes some sense: If those customers had to wait in line, they’d probably miss their train and the company is out a sale. But from a customer service standpoint, it’s idiotic. The employees are always being yelled at – both by the people who are in a rush and by the people who are waiting patiently. If they simply banned line-cutting altogether, then everyone would accept that they need to get there early and the whole process of ticket sales would be much more orderly.

Another example: When we were flying out of Irkutsk, Oksana’s check-in bag weighed in at 21.5 kilos. The airline attendant behind the counter wanted to charge her an extra $25 (or whatever), but Oksana wouldn’t have it. We held up the line as we pulled stuff out of the bag until it dropped to 20 kilos. It took some time, too. Our packs are stuffed from the top, down.

Oksana muttered some things under her breath at the woman, but she just sat there and waited. As far as she was concerned, she got a 5 minute break from helping customers and she didn’t care a bit that the people behind us were going to be more irritated when they reached her.

After checking in, we still had a few hours before we needed to be at the gate, so before we went through security, Oksana dug out her iPhone and checked the airlines’ regulations on overweight bags. She discovered that the limit was 23 kilos, not 20!

She marched right back up to the counter and asked the woman why she’d made her take items out of her bag if it was under the limit. Her response? It was Oksana’s fault. It’s the passenger’s responsibility to know that the airline-stated limit is 23 kilos!

(Talking it over later, we decided that this might better fit in the “corruption” instead of the “bad customer service” category. I’m pretty sure she planned to pocket the oversize baggage fee.)

Shopping

Moscow, of course, is now a modern capitalist metropolis. Change the language and you would have a hard time telling it apart from New York or Los Angeles. The shopping there was the same as any other big city in the world.

Out in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, though, I noticed something peculiar. While malls have begun to pop up all over the city, they’re different on the inside than we’re used to in the States.

Instead of having large department stores and franchise businesses, most malls in the Russian Far East are still stuck with the old market mentality. Think “cell phone accessory kiosks,” on a mall-wide scale. Instead of having Wal-Mart and McDonald’s move into the mall and wipe out the all the mom-and-pop operations in town, it’s like all the mom-and-pops just picked up and moved their tiny businesses inside the mall!

Even some of the supermarkets are stuck in this mode of thinking. On the outside, a supermarket may look just like a Safeway or a Winn Dixie, but when you go in, you realize that each aisle has its own vendor. Rather than fill your cart with what you want and pay for things near the exit, you instead only put them into your cart after they’ve been paid for. Because there’s more than one business under the roof, there may be three delis, two butchers, and five bakeries inside the same supermarket. Buying a package of M&Ms isn’t a straight-forward process, either. You’d do yourself a favor by shopping around, because they might be cheaper the next aisle over!

That said, you can see that they might be leaving the market stall model behind. Another supermarket conducts business in the traditional way (However, with tiny shops placed side-by-side along the entire perimeter, it appears that they just can’t quite let go of the old market mentality.) Also, there’s a Cinnabon in one of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy’s malls, too. Their sticky-sweet cinnamon buns herald future changes, I have no doubt!

Really enjoyed this post. You always get a different perspective on a country when you are traveling with/ staying locals. I am a Law & Order addict… hilarious that they kept the chung-chung noise but re-did everything else.

Arlo, This was a good read! I laughed out loud several times! (toasting the freshness of the salad…wearing orange from head to foot) The part about the fresh tomatoes and other garden fare made me homesick for my childhood in TX where we ate awesome fresh fruits and veg all summer. Yummy! Also interesting to think about the implications the cars not consistently on the same side of the car!

Glad you both liked it! Honestly, I didn’t expect anyone to stick with it!

Arlo, thank you for a great laugh! Fascinating post! Keep them coming!

Daniel

Glad you liked it Daniel. Just posted the one on Laos, now I only have 4-5 more to go! (Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, Singapore, and possibly Australia… though I’ve already written one on Oz after my first trip down under in 2008.)