Thoughts on Namibia

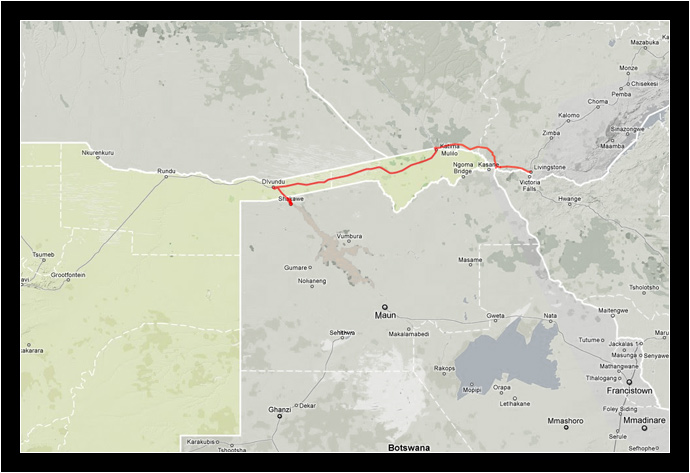

Believe it or not, I don’t think we took even a single photo in Namibia. So, here’s our GPS track, instead!

Our time in Namibia amounted to just one day as we decided the best way to get from Botswana to Zambia was via the Caprivi Strip. The Caprivi Strip is a strange stretch of land that doesn’t seem like it should belong to Nambia at all, but it has a very straight road through a wilderness preserve that leads right to where we were going. Getting there was a day-long adventure, however.

Early in the morning, we were dropped off at a remote border outpost between Botswana and Namibia. Getting our respective exit and entrance stamps turned out to be the easy part. When we asked how to get to the next town in Namibia, a very friendly border agent said, “Oh, you’re just a little too late. Why, a car went by just a half hour ago!”

No buses, no taxis. Waiting for a car and asking if you can ride along is business as usual way out there.

It took another hour or so, with us sitting on the curb by our bags, but eventually some kid drove by in a 90s-model Honda SUV. There were already four people in the car, but Oksana asked if we could ride along. I volunteered to climb in the back with the bags.

Once we started driving, I saw two things that gave me second thoughts about our ride. First, the driver was using the emergency hand brake to slow the car. I stared with dread fascination whenever he attempted to pass slower vehicles around blind curves. Nothing was scarier than watching him yank up the e-brake, in the face of oncoming traffic, to get us back in our lane.

Except, perhaps, realizing that both the driver- and passenger-side airbags had been previously deployed.

Let’s just say that we were quite happy to be dropped off at the next gas station-slash-supermarket in the middle of nowhere.

We waited at that gas station for a good couple of hours, trying to find a ride to Katima Mulilo, at the other end of the Strip. Oksana spoke with a pump attendant that said a bus would be along eventually and promised to keep an eye out for us. I checked on the ATM in the supermarket, but it was turned off. At least we were able to exchange the rest of our Botswana Pula for Namibian dollars, albeit at a horrible exchange rate.

While waiting, we had a nice conversation with a doctor from South Africa traveling with a guy from New Zealand (who were going the opposite direction) and chatted with a volunteer from Switzerland who was also trying to find a ride to Rundu. Eventually, I walked up to the gas station and asked the driver of a minivan if he was going our direction. He was, but his tank was empty. Would we be willing to pay for half a tank?

That came out to be 250 Namibian dollars, which I knew was more than the ride was worth. However, it was almost noon and we wanted to make sure we made the next border crossing before it closed for the night. I cleared it with Oksana first, then we took him up on his offer.

It turned out to be a great decision. Josef, our driver, and his girlfriend, Natasha, were both Zambian college students returning from a holiday spent in Namibia. Natasha was shy, but Josef was both curious and well-educated. We had a delightful conversation about Russia, the United States, and, of course, the next country on our list, Zambia. In the meantime, we watched the wilderness roll by outside our windows. Three huge rivers came and went (the Okavango, the Kwando, and the Zambezi), and as we got closer to Katima Mulilo, the bush became speckled with traditional reed-and-mud dwellings.

At a military checkpoint along the Kwando River, a fat, officious commander left his shady seat to talk with our driver. He could have been an extra in some Hollywood movie, credited as “Self-Important African Military Officer.” I didn’t speak the language, but I could tell what was going on because the conversation was so short.

“Where are you going?” He demanded.

“Katima.” Our driver was playing it polite for now, but I could tell he was deciding if he should dip down to subservient.

“You will take this boy and drop him off along the way.” He shouted over the hood of the van and waved a boy of about 14 over. Dressed in decent clothes and carrying a messenger bag, I took him for a shy kid returning home from school in the big city. He slid open the side door and hopped in next to Oksana.

The officer, having solved the day’s crisis, walked heavily back to his shade as we drove away. We dropped the boy off only about 10 kilometers down the road where he sheepishly thanked our driver and started off down a lonely dirt road.

Late in the afternoon, we finally arrived in Katima Mulilo. Josef was taking Natasha straight to the border, but we knew from our guidebook that the Zambian side only accepted Zambian, U.S., and South African currencies. We didn’t have enough cash to pay for each of our USD$80 double-entry visas, so we asked to be dropped off in town, instead.

With friendly waves goodbye, they left us at a sizeable strip mall in Katima where we piled up our bags outside a bank. I tried two ATMs while Oksana kept an eye on things, but neither one would dispense U.S. dollars. There was an information desk inside the bank, so I took my questions to them. Can we pay at the border with Namibian dollars? No. If I withdraw enough Namibian dollars from the ATM, can you exchange them for dollars? No. We’re out of U.S. dollars today; maybe tomorrow morning we’ll have more. Will the border accept South African Rand? Yes. Can I exchange Namibian dollars for Rand? Yes, if you hurry. We’re closing.

The Namibian-to-Rand exchange rate was 1-to-1. I don’t know why Zambia won’t accept the currency from a neighboring country, especially since it seems just a solid as the Rand. At any rate, I converted the money in time. With enough cash in our pockets to make it through immigration, we began looking for a way to get to the border. Luckily, it took only five minutes this time, as someone loading their car up with groceries from the Pick N’ Pay offered to run us over.

We got our exit stamp on the Namibian side and started to walk across the border when all manner of taxi drivers swarmed us. We thought it was a scam. Most stretches of no-man’s-land between borders are only a couple hundred meters, but as we passed through the gate, we realized it was more like a kilometer to the Zambian outpost. The heat of the sun beat down on us and our heavy packs, so when a tiny minivan pulled up and the driver offered to take us to immigration, wait for us, and then take us to the bus station, I decided not to even haggle down his first offer of 10 Namibian dollars.

Zambian immigration was exactly like what you’d expect a third-world border office to look like. A fat (though amiable enough) man in a military uniform sat behind a tall desk, slamming his stamp down on an endless stack of papers. Fractured windows let the sunlight in, illuminating motes of dust that were being pushed around by a slow ceiling fan. We were in the office for a good 20 minutes and never saw another tourist.

I told the immigration official that we wanted to pay in Rand instead of dollars and he “tsk, tsked” us. “You can do that,” he said, “but the exchange rate… it is no good. I have to use the money changers outside. They are all thieves.”

Why an official branch of the government couldn’t use a bank, I don’t know. “How much do you think it would be for both our visas?” I asked.

He thought it over for a few seconds and said, “900 Rand?”

I managed to keep a straight face as I handed over the money. We had planned to pay 1,200 Rand.

While he was hand-writing the visa information into Oksana’s passport, I had a thought. “Oksana,” I whispered, “Will you ask him if we can come back to Zambia again if go see the Zimbabwe side of Victoria Falls?”

When she asked, the immigration officer said, “Oh! You want a double-entry visa! That will cost more!”

That deal we thought we were getting? Not looking so good. In fact, when he quoted us the new price, we didn’t even have enough Rand to cover it. We were forced to dip into our emergency stash of U.S. dollars to pay for Oksana’s visa. Silver lining: At least we only got burned on the exchange rate for one visa.

Finally free to enter the country, we walked back out into the dirt parking lot. True to his word (probably because we hadn’t paid him yet), our driver was still waiting to take us to the bus station so we could catch a ride to Livingstone. As we were crossing the Zambezi River, he tried to use his broken English to tell us how bad an idea it would be to actually take a bus. Instead, he assured us, we should be looking for a shared taxi!

The day had been stressful up to this point and Oksana and I had different reactions to this dilemma. She wanted to argue with him, to understand why he didn’t want to take us to a bus. I just wanted to give in, go with the flow, and trust that we’d get there eventually.

On the other side of the river, things changed and we realized that we hadn’t been mentally prepared for Zambia. One glance at the controlled chaos bordering both sides of the street was all it took for us to realize that South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia were far ahead of this new country. Things may be cheaper, we realized, but they were about to get more confusing and less comfortable.

Our driver dropped us off next to a compact blue car with half a dozen people standing around it. He confirmed for us that it was going to Livingstone and told us it would be leaving “very soon.” We negotiated a too-expensive price (because we only had Rand) and then tried to settle the bill with our previous driver. I gave him a 20 dollar (Namibian) note, but he couldn’t make change in the same currency. He offered me the rest in Zambian Kwacha, which was helpful because we didn’t have any on us yet, but I knew that he was screwing me out of a dollar or two. I rationalized it away; you can’t expect to get the best deals on border crossings. The best you can do is get away as quickly as you can.

This last ride of the day turned out to be the longest and most entertaining.

Our car was comically small, but that didn’t stop the driver from making the most out of the ride to Livingstone. Aside from the well-dressed passenger riding with him up front, Oksana and I were crammed into the narrow back seat with a young guy that knew as little about English as he did about deodorant. A drunk guy crammed himself into the tiny hatchback space behind our seat, along with Oksana’s big pack. Two of the larger bags, including my own pack, were lashed to a makeshift roof-rack made from bungee cords and, I kid you not, broken broomsticks.

As we set off, the car’s cushy shocks gently bounced us up and down with every bump in the road. I was convinced that we were going to lose my pack and watched the shadowy silhouette our car cast along the roadside until the sun set an hour later. After dark, as we endlessly swerved around giant potholes I thought of as Elephant Traps, I listened for tumbling sounds from the roof. Everyone in the car took turns telling me to stop worrying, “This is Zambia. Everything is safe in Zambia!”

The well-dressed passenger up front went on to say how beautiful Zambia was while he crumpled up his empty Coca-Cola can and threw it out the window.

Our fellow passengers were as curious about us as we were about their country. We learned that there were seven official languages and something like 77 different tribal languages spoken in the country. On the spot, they decided to teach us phrases in at least 3 of them. We were bombarded by different words and sentences and I got the impression that they were genuinely surprised we weren’t able to memorize them all as they came at us. I was almost relieved when the driver put an end to the conversation by cranking up the Zambian techno music. Almost.

Before we got to Livingstone, we pulled of the main road toward another border crossing near the Chobe River. The driver explained to us that our well-dressed passenger wanted to exchange some money for U.S. dollars and the best place to do that was at the border. By the time we got there, the border was closed and there were dozens of semi-trailers parked in the dark. Our well-dressed passenger divided his time between furiously texting on his Blackberry and calling out to various unseen drivers.

We still didn’t have any Kwacha for our time in Zambia, so finally I asked him, “How much money are you looking to change?”

“2,000 dollars. Do you think you can handle that?”

“No. Um… no. Sorry.” And even if we could, I wouldn’t tell you.

We sat back and waited. He never did get his money. Before long, we were back on the road, dodging those elephant traps in the dark again at 120kph.

When we arrived at Livingstone, the dark never let up. There was a city-wide power outage and we had no point of reference when we drove into the city. Fortunately, our driver knew the hostel we had picked from our guidebook: Livingstone Backpackers. He dropped us off at the gate. My backpack was still on top of the car and we had to use my flashlight and Swiss Army knife to cut it down.

The hostel we read about in our guidebook had private rooms, but apparently that wasn’t true in real life. We’d had a very long day and all we wanted was a few hours of uninterrupted sleep. The power outage made it difficult, but through text messages the receptionist was able to ascertain that their sister hotel, Fawlty Towers, still had rooms available. One of the night security personnel even walked us over in the dark.

Fawlty Towers was a welcome sight. It had a generator and was lit up like a Christmas tree in a darkened room. There was a big TV playing music videos over the bar, guests were hanging out around a pool table… even the wi-fi worked!

As we were dropping off our bags in the room, the lights came back on, so we crossed the street to an ATM and withdrew a big pile of Zambian Kwacha. When we paid the receptionist for our room, it was the fifth international currency we’d used that day.

We bought some internet time, checked our email with the best connection we’d had since leaving South Africa, and turned in early. It had been a long day and we were exhausted.

Thoughts on Namibia

Oh yeah, hey! That was the whole reason I started writing this post – to describe the things I observed in Namibia. Well, with only one day on the ground, the list was very short. Guess that’s why I got sidetracked with that little story above. Anyway, here we go:

Transportation

Transportation is easy to come by in Namibia if you’re patient. I’m sure there are buses and taxis available in the bigger towns and cities, but we never had the pleasure. While we didn’t stand by the road with our thumbs out, we did basically hitchhike from place to place and it seemed perfectly normal to do so.

That’s it. No big revelation. You can get a ride in Namibia if you ask enough drivers.

Language

In all fairness, this may not be a Namibia thing – I heard it on TV. In my Botswana post, I may have mentioned in passing one of those African “clicking languages.” I don’t think we ever did interact with one of the cultures that uses those sounds, but I did catch a news broadcast with one while standing in line at the bank.

It. Was. AMAZING!

Of course, I have no idea what was being said, but the sounds! If I were to try to describe it, I would say that it was very much like hearing one person speaking a foreign language while another person stood next to them, randomly clicking their tongue against the roof of their mouth every second or two.

In learning Spanish, I’ve found certain sequences of sounds (usually revolving around the rolling ‘R’s) to be hard to put together because my tongue just can’t move fast enough. I could tell I would have had a much harder time trying to put the clicks and pops of that African language into a smoothly-said sentence!

The Handshake

Personal space is different in every country we go through and sometimes the casual touching that would feel comfortable in one country would bother someone from another. When you understand the country’s customs, it’s not too shocking when you see, say, two guys walking arm-in-arm down the street. If you saw that in the United States, you’d be safe in assuming the couple was gay. Not so, in other countries.

In Namibia, they have a strange – Not strange! Interesting! – custom with respect to handshakes. Let’s say you haven’t seen someone in awhile. When you meet that person on the street, you wouldn’t think it out of the ordinary to shake their hand, right? Well, in Namibia, they do that, too.

Only they don’t let go.

Again, while I was standing in line at the bank, I watched two guys come together outside the large plate-glass windows. They stepped up to each other, shook hands – up, down, up, down – and then just held hands. While they talked, facing each other. For at least 5 minutes.

Doing that would make me so uncomfortable. Again, I can understand the cultural differences we have on an intellectual level. I can even delight in seeing them. But that doesn’t mean that I can just set aside 38 years of personal-bubble development and embrace them. I’m sort of glad I never had the chance to offend anyone in Namibia by letting go of their hand too soon. (Or by hanging on with one extremely nervous and sweaty palm!)